From Carbon Tracker

Navigating Peak Demand: the oil and gas industry enters its post-imperial age

Most things may never happen: this one will

Philip Larkin, Aubade

Despite a decade of noting the risks of over-extending investment in oil and gas production, and risking trillions of dollars in stranded assets, Carbon Tracker finds itself as 2023 ends picking through the final options available to the industry as oil demand closes in on its peak, before entering decline.

Ahead of COP 28 (the 28th UN Climate Change Conference) in Dubai we released two major reports Navigating Peak Demand – a follow up to our previous assessment in early 2022, Managing Peak Oil, and PetroStates of Decline

We will focus on these reports below, and also review a related blog which highlights the cautionary tale of business as usual oil investment in the UK: Are more UK oil and gas licences really the answer?

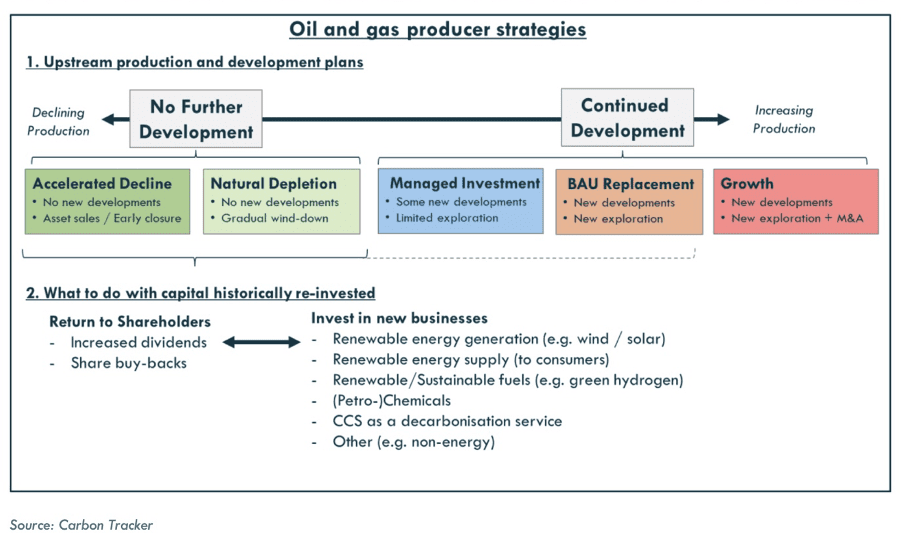

In Navigating Peak Demand we consider two scenarios of future oil demand representing a moderate and a fast pace of transition – and what it means for the industry and investors if they stay with today’s business as usual (BAU) strategy.

Global oil and gas demand has been a low-growth story for many years: even without new energy sources the competing forces of expansion and decline have pushed the industry into an equilibrium, a flat-line pattern.

Yet now with the addition of fast-paced renewables, that flat pattern is turning into a peak followed by decay.

Over the past 10 years renewable energies – mainly wind, solar, batteries and heat pumps – have dropped in cost by 50-90%. Their exponential deployment now means for example that in Europe wind and solar alone provide more power (22%) than fossil gas (20%) for the first time, and global investment in wind and solar alone now outpaces that of oil and gas for the first time too in absolute value at over $500bn pa.

Industrial scale new renewables, allied with mainstays of nuclear and hydropower, are now forcing an energy industry tipping point, and at a fast pace of change. Together these forms of energy already supply 18% of primary energy and are on course to produce 30% of primary energy by 2030.

A key example: to meet the Net Zero requirements in IEA scenarios the deployment of wind and solar will need to treble in capacity by 2030 from 3.6TW to 11TW. And that is exactly what many analysts and governments now expect to happen.

Renewables allow mass electrification in various sectors beyond power, such as transport and heating to force fossil fuels on to a plateau of demand, and in many regions and sectors already into a full-scale decline.

An unbiased observer looking at the energy landscape will now see fossil fuel peaks emerging like a mountain range coming into view: peak combustion engine car sales in 2017, peak gasoline sales 2023, peak emissions in the power sector likely 2023, peak emissions across the energy sector also possible in 2023, probable by 2025.

Peak emissions to be clear are a lagging indicator of change: if emissions have peaked it is very likely that fossil fuel consumption has peaked in advance.

Commentators such as the IEA, typically cautious in this space, announced in their latest World Energy Outlook (again) that no new oil and gas exploration is required to meet the declining future demand.

[…] (Please click at the bottom to continue reading full article at the source)

Coda

We began with Larkin’s poem on how things reliant on earth-bound finite resources – a human body, an oil field – will always have an end.

To paraphrase: Most things may never happen: but Peak Oil Demand will.

——————

References

Carbon Tracker

Navigating Peak Demand

Peak Demand Press Coverage

Petrostates of Decline

Managing Peak Oil

Are more UK oil and gas licences really the answer?

Driving Change

Other References

FT Petrostates Report Review

IEA WEO

IEA Peak Transition

Carbon Brief

The post Energy Monitor December 2023 appeared first on Carbon Tracker Initiative.

[...]

Read the full post at Carbon Tracker.