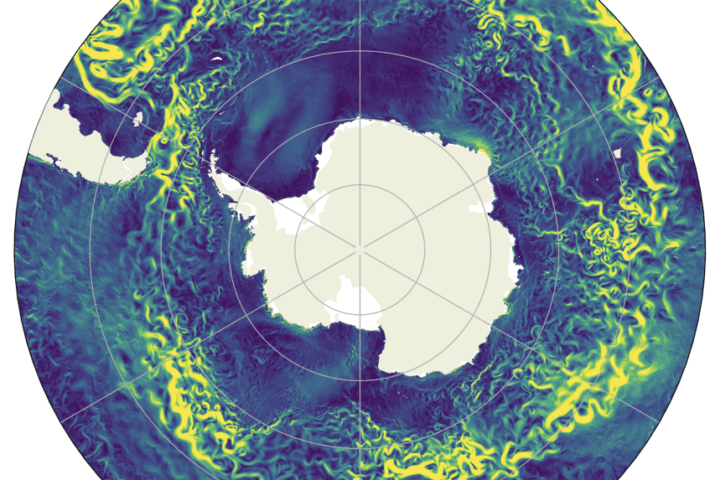

On Earth Day next year, expert judges will decide who should get the biggest incentive prize in history—$80 million for removing at least 1,000 tons of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. They can use air, land, oceans or rocks, with a plan to scale up to gigatons annually. The XPRIZE for Carbon Removal is a $100 million effort funded by Elon Musk to help fight climate change and restore the Earth’s carbon balance. Since its launch in 2022, more than 1,300 teams have registered, over 300 of which have indicated they are ready to demonstrate a working system. If all goes to plan, the competitors should remove a total of nearly four megatons of CO2 this year.

Climate competitions and contests have never been more popular, with their number and value growing exponentially since 1970—even Prince William has one. Part of their popularity with funders might be that prizes seem to generate more positive publicity—and attract less critical scrutiny—than traditional research grants.

All of which raises some novel questions. Are prizes really an efficient way to move the carbon needle? Or just a sideshow from the tough business of reinventing economies to be more sustainable?

• • •

Yes—And We’re All Winners

1. That lightbulb moment. History is studded with examples of prizes kickstarting progress. A Parisian confectioner invented canned food in the early 19th century after Napoleon offered 12,000 francs to anyone who could preserve food for his invading troops. And Charles Lindbergh’s epic trans-Atlantic flight in 1927 was inspired as much by a $25,000 prize (worth about half a million dollars today) as by the thrill of exploration. Prizes can help the climate, too. In 2008, the US Department of Energy launched the $10 million L Prize to replace the 60-watt incandescent bulb. Within three years, Philips developed an LED bulb that consumed 83% less power. Within four, the bulb was on shelves and within five, it was already being outclassed by more efficient rivals.

Read the full post at Anthropocene.